Hi everyone,

During Notes of Rest at The Practice Church on Sunday, I reflected on a disturbing yet telling experience I had around Black music recently. Last week in Chicago when I was waiting for my brother Nova Zaii’s set to start, the DJ put on A Lot by 21 Savage. This song is confessional and celebratory from 21, where he recounts having survived horrific violence in Atlanta. What has always disturbed me are the two lines from the song that say “how many times you got shot?/A lot/how many n*ggas you shot?/a lot.” It’s so casually stated in this song that Savage has survived this horror and has put others through horror too that it has always felt odd that it was in one of his most popular songs, especially one over the East of Underground sample “I Love You.”

But what made it worse that Thursday night was when I saw this White man walking around bobbing his head to it absentmindedly amidst a room comprised largely of Black folk. Now, to be fair, I don’t know the guy’s story. Maybe he grew up shooting and getting shot just like 21 Savage. But whether he did, seeing him bob his head to this litany of horrors stemming from Black poverty got me thinking about the major festival Lollapalooza that was happening right up the street, where Kendrick Lamar would be performing that next night to a sea of White suburbanites who flock to the city to hear him and others talk about their Black trauma and pain and sing along with him. They will then get back in their cars and drive back to their safe(-ish) suburbs and the hood will continue being a place where the Kendrick’s and 21 Savage’s shoot and get shot. (Thankfully Chicago is having less homicides this year, but still too many.)

This song is also a confessional, but a way to give praise to God through conversion. What’s it mean to find this song beautiful?

I brought up my disturbance in Notes of Rest in a White suburban context because I wanted people to think about how Black music forms us. For 21 Savage, it’s clear that this music is some kind of balm for his soul; he even says later in that same song that he discovered he could get paid for rapping over beats. But what I worry about is how Black folk can be formed by what rapper and pastor J. Kwest calls the re-traumatizing nature of these songs, and how White folk are the main customers who patronize hip-hop. What does it do to form White life to hear Black folk turn their pain into this trauma that they can then sing along with?

To be clear, Black folk talking about their trauma is not what disturbs me. We write books, teach classes, sit for interviews, show caskets of our mangled children on national news, and do all other kinds of work that exposes our pain to the world. So Black folk publicly airing our wounds and our questionable decisions to mainstream audiences is not the direct issue.

Rather, I am talking about the problem of Black music being entertaining and participatory in nature. How is Black music forming us through its invitation to us to sing along with the people on stage, or take delight at the beautiful sounds coming from the bellow or shouts on stage?

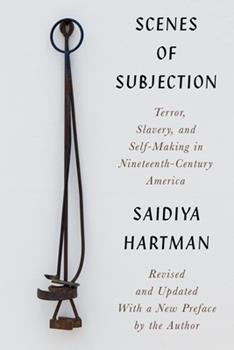

In Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth Century America, Saidiya Hartman observes that Black slaves who could play music (oftentimes the fiddle) were highly sought after by slave owners. They would be bought and put onto plantations and forced to play while the other slaves were forced to dance along. It was a way of establishing order - of keeping them in line. It was also a way of crystallizing the mindset of the White ruling class to see Black music as having this formative power over Black bodies. In short, Black music has always had formative potential to shape how this country sees itself and sees those who have built it.

Let’s compare this historical reality of Black music to the hypothetical for some other American sub-cultures who too have been feared and loathed by WASP America at some point. Can you imagine Chinese Americans, Italian Americans, or Irish Americans getting on the mic and getting paid millions of dollars to sing about pimping their own women or selling drugs in their own communities in order to survive? We all know Black folk aren’t the only ones poor, who sell drugs to their own and commit dangerous acts of violence. But the economic apparatus surrounding my people’s music, dating back to slavery, can make it seem like we are uniquely so. And what’s even worse, it can inure the country to antiblack violence. This is the malformation capacity of Black music: to listen to someone’s pain and not have to do anything about it.

But that is not the only way Black music functions. What happens when we hear this social, physical, emotional, and spiritual pain from Black music and see it as a charge to change? If you listen to hip-hop and find it beautiful, ask yourself what makes it beautiful to you. Moreover, how does/can that sense of beauty shape your ethics?

Let God shift something in you through Trane’s sound. He is playing for something deep at stake. Sometimes you don’t need words for transformation.

In 1 Samuel 16: 14-23, when soon-to-be King David played his lyre for the troubled King Saul, he brought him relief from his pain. But David’s very presence in Saul’s court was a charge to the existent King that change needed to come. King Saul was on his way out because of his disobedience to God, and David on his way in as the newly anointed leader. The music, therefore, was both a balm and a charge. Can we hear the Holy Spirit speaking to us through Black music as both a balm to those deeply troubled and as a charge to those who need to listen up? For the sake of the future of my people, I pray so.

abundantly,

Julian

P.S. The Fellowship is on and popping! Post 2 was about how God’s deepest note for us is through salvation in Jesus from our unrest.

What’s Next:

Notes of Rest Virtual Class at Candler School of Theology, 5 consecutive Mondays starting Oct 9

A powerful piece of writing. Thanks for this and all you do. Much appreciated.